Two weeks after the capture of Booneville, Gerenal Lyon cut off communication between the Southern men on both sides of the river. Col. John D. Stevenson was left in command of the river from St. Louis to Kansas City with orders to hold the principal towns. Lyon then began his march on the Southwest. He went to the Grand River crossing, south of Clinton, pushing forward toward Springfield. Meanwhile Sigel had been routed at Carthage. At the crossing of the Osage, a few miles above Osceola, he learned of Sigel's defeat. He ferried his men and trains across the river and without rest marched his men twenty-seven miles without stopping. In the heat of a July afternoon they stopped for a few hours. The march then resumed and did not halt until the outfit was within thirty miles of Springfield and fifty miles from the crossing of the Osage only to learn that Sigel was in no immediate danger. Lyon and his troops entered Springfield with great showmanship. His escort, which was composed of St. Louis German butchers were giants in size and ferocious in attitude mounted on powerful iron horses, armed with big revolvers, huge swords, and dashed through the streets of the town held by Sweeny.

When General Price left Lexington he went directly to General McCulloch's headquarters. Enroute he was joined by squads and companies, when he reached Cowskin prairie, he had about 1,200 men with him. He learned that General Pearce, commander of the military forces of Arkansas, was near Maysville with an Arkansas brigade, and leaving his men in camp on Cowskin prairie he went there with escort. General Pearce received him cordially and informed him that General McCulloch had left his headquarters at Fort Smith and would reach Maysville the next day. General Pearce loaned General Price 650 muskets. General Price returned to Cowskin prairie, organized his men and placed those he could arm under command of Col. Alexander E. Steen, a young Missourian who had a short time before resigned from the regular army. The next day General McCulloch, in advance of his troops, reached General Price's headquarters, and at once agreed to aid the Missourians. General Pearce also agreed to aid them with his Arkansas force. The next day on the 4th of July, McCulloch and Pearce entered Missouri with Churchill's mounted Confederate regiment, Gratiot's Arkansas infantry, Carroll's mounted regiment and Woodruff's battery; reached Price's camp the same day, were joined by him, and continued their march northward to rescue Governor Jackson and his party. Under the impression that the governor was pressed by Lyon on one side and Sigel on the other, McCulloch left his infantry behind, and he and Price pressed forward to his relief. On approaching Neosho, McCulloch sent Churchill with two companies to capture a company Sigel had left there. This Churchill did without firing a gun. He not only took 137 prisoners, but captured 150 weapons and seven wagons loaded with supplies. At the break of day on the 6th, the march continued on to Carthage, but during the day it was learned that Sigel was defeated. McCulloch and Pearce with their troops then returned to Maysville, and Price took command of the Missourians and returned to Cowskin prairie to organize the companies and regiments. He had no arms, no military supplies, and no money to buy any. The men never expected to be and never were paid. But men and horses had to be fed, and on Cowskin prairie there was little but green corn and poor beef upon which to feed them. Quartermaster-Gen. James Harding and Chief Commissary John Reid went to Fort Smith, Little Rock and Memphis in search of supplies. The men and horses managed to live on what the country afforded, and while General Harding was absent, Col. Edward Haren acted as quartermaster-general, and by his activity, industry and unfailing courtesy did wonders in providing the absolutely necessary supplies, and making the men contented. All of General Price's staff, except Colonel Henry Little, were civilians, and knew nothing of the military duties their position imposed upon them. But they were willing and learned rapidly. The Granby mines furnished lead, and Governor Jackson's forethought had provided a supply of powder. Some artillery ammunition captured served as a pattern, and the cannoneers were soon able to make the necessary ammunition for their guns. Notwithstanding the embarrassments and drawbacks, the work of organization went steadily on, and by the last of the month the State Guards assumed form and substance and became an army of 4,500 armed and 2,000 unarmed men, anxious to meet the enemy. They were a motley crowd. There was hardly a uniform among them. The insignia of even a general officer's rank was a stripe of colored cloth pinned to the shoulder. General Price left Cowskin prairie on the 25th of July, and in three days reached Cassville. There he was joined by Brigadier-General McBride with 650 armed men, which made his force over 5,000. General McCulloch reached Cassville the next day with his brigade, amounting to 3,200 men, nearly all armed. General Pearce was within ten miles of Cassville with his brigade of 2,500 Arkansas troops, together with two batteries, Woodruff's and Reid's. The entire force amounted to nearly 11,000 men, beside the 2,000 unarmed Missourians, who went with the army with the expectation of getting arms after a while. Price, McCulloch and Pearce each had an independent command, but they agreed upon an order of march, in conformity with which the combined forces began their advance on Springfield, fifty-two miles distant, on the last day of July. The first division, consisting of infantry under command of McCulloch, left Cassville that day. The other divisions, commanded by Pearce and Steen, left the following day, and Price, without taking any command, accompanied Steen's division. As soon as Lyon reached Springfield he began writing and sending representatives to St. Louis and Washington demanding reinforcements. But his demands received little if any attention. General Fremont was in command of the Western department, and did not seem disposed to help him. When assured that Lyon must and would fight at Springfield, he simply replied: "If he does he will do it on his own responsibility." Lyon said. "If it is the intention," he said, "to give up the West, let it be so; Scott will cripple us if he can." At last two regiments, Stevenson's at Booneville, and Montgomery's at Leavenworth, were ordered to report to him at Springfield. But they never reached him. It was a question with Lyon whether to fight or retreat, and the first alternative seemed to be safer than the last. His only line of retreat was to Rolla, 125 miles distant, through a broken, rugged country, with the probability that Price's and McCulloch's mounted men would be thrown in his front, while their infantry pressed him desperately in rear. Besides, to retreat was to give up all he had gained, to allow Price to return to the Missouri river with an army and to begin anew a fight for the possession of the State. He had 7,000 or 8,000 men, thoroughly armed and equipped, and he determined to risk defeat rather than turn back. On August 1st he learned that McCulloch, Price and Pearce were advancing on Springfield. He was deceived as to their line of march, supposing they were advancing by different routes, and determined to attack them in detail. With this view he moved out, his force consisting of nearly 6,000 men, infantry, cavalry and artillery. When he got within four or five miles of them and learned he was mistaken, he stopped and waited for them. But he was deceived again. It was the advance guard under Rains which was in front of him. The main body was in camp twelve miles back. The next day he moved to within six miles of the Southern force, but not being able to learn anything about its strength, and fearing he might be flanked, he determined to return to Springfield, which he did the next evening. The united Southern forces had remained in their position during this time, and had been reinforced by Greer's Texas regiment. While the two armies were maneuvering and watching each other, General Price was anxious to attack, but General McCulloch declined unless Price would consent to give him the command of the combined army. At last, after a good deal of wrangling, General Price yielded, reserving to himself, however, the right to resume command of the Missourians whenever he chose. Believing that Lyon was still in front of him, McCulloch marched at midnight of August 5th, expecting to surprise and attack him at daybreak. But he soon learned that Lyon had left the day before for Springfield. He followed him until he came to Wilson's Creek, where he encamped. There the army remained three days, the dispute all the time going on between Price and McCulloch, the former insisting on attacking, and the latter declining to do so. At last McCulloch yielded and ordered the army to be ready to move that night, August 9th, at 9 o'clock. But before that time it began to rain and the order was countermanded, chiefly because the Missourians had no cartridge boxes, but carried their ammunition in their pockets, and it was liable to be ruined if it rained hard. The troops lay on their arms during the night, awaiting the development of events. Late in the afternoon Lyon moved out of Springfield, marched about five miles west, then turned southward across the prairie, and about midnight came in sight of Rains' camp fires. He had turned McCulloch's left and was in his rear. Sigel, with two regiments of infantry, six pieces of artillery and two companies of cavalry, aggregating about 1,500 men, had made a similar movement and turned the right flank of the Confederates. He planted a battery on a small hill within 500 yards of Churchill's camp, disposed his men so as to capture every one coming or going, and waited for Lyon to begin the fight. Lyon halted in sight of Rains' camp fires until dawn and then resumed his march. The Confederates had withdrawn their pickets in anticipation of moving themselves, and when the movement was abandoned had not sent them out again. Just at daylight Rains for some reason became suspicious, and sent a staff officer with a small detachment to reconnoiter. The officer soon came back in haste and informed him that the enemy were advancing in force with cavalry, artillery, and infantry, from the southwest. Rains instantly informed General Price, and formed his own command. McCulloch was at Price's quarters, and this was the first intimation either of them had that Lyon and his army were upon them. McCulloch discredited the information, and said he would go himself and see about it, but before he could mount his horse another messenger came with the information that Rains was falling back before overwhelming numbers, and at the same time came the report of Lyon's artillery, which was followed in a moment by the guns of Sigel, who had opened fire on Churchill, Greer and Brown, and was driving them out of the little valley where they were encamped. Lyon meanwhile was driving Rains. Instantly McCulloch and Mcintosh mounted and galloped to take command of the Confederates on the east side of the creek, and Price ordered his infantry and artillery to follow, rushed up Bloody Hill--a considerable mound in the midst of the field and named because the battle roared and broke into a pool of blood around it. Cawthorn's brigade was falling back fighting in hope of holding the enemy in check until infantry and artillery could come. These were forming, and they came up the hill with a rush. First came Slack, with Hughes' regiment and Thornton's battalion, and formed on the left of Cawthorn; then Clark, with Burbridge's regiment, and formed on the left of Slack; then Parsons, with Kelly's regiment and Guibor's battery, and formed on the left of Clark, and on the extreme left of the line McBride took position with his two regiments. Shortly after Rives, with some dismounted men, reinforced Slack; and Weight-man, with Clarkson's and Hurst's regiments which had been encamped a mile or more away, came up at a double-quick and formed between Slack and Cawthorn. In the meantime Woodruff had taken position with his Arkansas battery on an elevated point of land overlooking the field from the east, and at the first sound of Totten's guns had opened a fire on Lyon which retarded his advance and greatly aided the Missourians in getting into position. The battle was now fairly set. The opposing forces were nearly equal. Price had about 3,500 men, and Lyon, deducting the 1,500 under Sigel, had about 3,500. The lines were not more than three hundred yards apart, but a heavy undergrowth of timber separated and concealed them from each other. Price's men were armed mostly with hunting rifles and shotguns, and to make them effective it was necessary that the lines should be close together. Instead of advancing, Price waited for Lyon to attack. He did not have to wait long. In a little while the order to move forward was heard, and through the brush the enemy came. When they were within close range there rang out the sharp report of a thousand rifles, the heavier report of a thousand shotguns, and crack of innumerable pistols, the roar of Guibor's guns--and the day in the field Missourians had looked forward to longingly amid the disappointments and delays of months was before them, and they resolved to die or conquer where they stood. Rough and ragged and worn, the best blood of Missouri faced the enemy in that battle line. The hand that held the musket might be awkward, but it was steady. The men might not be able to maneuver, but they could fight. When one of them fell an unarmed man stepped promptly forward to take his place and his gun. For hours the fight went on. The lines would approach to within fifty yards of each other, deliver their fire and fall back a few yards to reform and reload. It was a succession of charges followed by a succession of repulses, with solemn intervals of silence between, as each side braced itself again for the desperate struggle. It was man to man and to the death. Price would not have retreated if he could, and Lyon could not if he would. He had risked everything on the desperate chance of battle, and had to fight it out to the bitter end. McCulloch's and Pearce's infantry were on the east side of the creek, where McCulloch had formed the men so as to meet Sigel's attack and to protect Price's rear, posting the Third Louisiana, McIntosh's regiment and McRae's battalion within protecting distance of Woodruff's battery, which was firing across the creek. He had not more than made these dispositions when a force of the enemy appeared, moving down the creek on the eastern side with the evident intention of charging Woodruff's battery. Leaving Gratiot to support Woodruff, he ordered McIntosh, with his regiment dismounted, the Third Louisiana and McRae's battalion to meet the advancing Fed erals. They charged and drove back Plummer's battalion of regular infantry and a regiment of Home Guards, with a loss of about 100 on each side. Plummer was severely wounded. Sigel had not been heard from since the first dash early in the morning. He had, in fact, taken position on the Fayetteville road to intercept and capture the Confederates after Lyon had routed them. His dispositions to that end were made with military precision. His battery occupied a commanding position, his infantry extended on both sides of the road, and a company of regular cavalry was on each flank. He was quietly awaiting results. After the affair with Plummer, McCulloch went in search of him. He took his own infantry, with Rosser's and O'Kane's Missouri battalions and Bledsoe's battery. Bledsoe placed his battery so as to command the enemy's position. Reid's battery was somewhat east of Bledsoe's. The infantry advanced to the attack and Bledsoe and Reid opened at point-blank range. Sigel was taken by surprise and his men thrown into confusion, and when McCulloch and Mcintosh, with 400 of the Third Louisiana and Rosser's and O'Kane's battalions, broke through the brush and charged his battery his whole force fled, abandoning the guns, some going one way and some another. Sigel and Salomon, with about 200 of the German Home Guards and Carr's company of regular cavalry, tried to get back to Springfield by the route they came, but were attacked by Lieutenant-Colonel Major, with some mounted Missourians and Texans, and again routed. Carr and his cavalry fled precipitately. Sigel with one man reached Springfield in safety. Nearly all the rest were killed, wounded or captured. In the meantime, the main fight on Bloody Hill raged fiercely. Though hard pressed, Price had not yielded a foot of ground. Churchill, who held a position on the left of the line,dismounted his men and moved them to the center, where the need was greatest. Price then advanced Guibor's battery in line with the infantry, while Woodruff continued throwing his shells over his line into the ranks of the enemy. Still the battle was not won. Lyon was bringing up every available man for a last desperate effort. Price asked for aid, and General Pearce, with Gratiot and his Arkansas infantry, came to his assistance. In getting into position Gratiot suffered severely. His horse and his orderly's were killed, his lieutenant-colonel was dismounted, his major's arm was broken, his quartermaster was killed and his commissary badly wounded. But the regiment took the position it was ordered to take and held it, though in half an hour it lost 100 out of 500 men. The fighting was now furious. In the words of Schofield and Sturgis, "The engagement had become inconceivably fierce all along the entire line, the enemy appearing in front, often in three or four ranks, lying down, kneeling and standing, and the line often approaching to within thirty or forty yards, as the enemy would charge upon Totten's battery and would be driven back." General Price was painfully wounded in the side, but did not leave the field. He only said to those who were near him that if he were as slim as Lyon the bullet would not have hit him. Weightman was borne to the rear dying; Caw-thorn and his adjutant were mortally wounded; Slack was desperately wounded; Clark was shot in the leg; Col. Ben Brown was killed; Colonel Allen, of General Price's staff, was killed by the side of his chief; Colonels Burbridge, Kelly, Foster and numerous field officers were disabled. But Lyon was worse hurt than Price. He had, however, risked everything on the chance, and in the shadow of impending defeat was determined to make a supreme effort to reverse the tide that was setting strongly against him. Dismounted, he was leading his horse along his battle line, speaking words of encouragement to his men, when his horse was killed and he was wounded. He was dazed by the shock, but quickly recovered, mounted another horse, and, drawing his sword, called upon his men to follow him. A moment after a ball struck him in the breast and he fell from his horse, and in another moment was dead. In the pause that occurred following Lyon's death, Price was reinforced by Dockery's Arkansas regiment, a section of Reid's battery and the Third Louisiana regiment. Thus strengthened, he was better prepared to hold his ground than he had been at any time during the day. The command of the Federal army devolved on Major Sturgis. He counseled with his principal officers and they decided to retreat. The order to withdraw was given at once and promptly obeyed, Steele's battalion of regulars bringing up the rear. For five hours the fight on Bloody Hill had lasted, and the dead of both armies lay upon it in piles. When it became known that the Federals were retreating and that the day was won, a great shout of exultation and relief went up from the men who had fought there, which reached the ears of Weight man where he lay dying, and he asked those around him what it meant. "We have whipped them--they have gone," he was told. "Thank God," he said. In another moment he was dead. Of him in his report, General Price said: "Among those who fell mortally wounded on the battlefield, none deserve a dearer place in the memory of Missourians than Richard Hanson Weightman, colonel commanding the First brigade of the Second division of this army. Taking up arms at the very beginning of this unhappy contest, he had already done distinguished service at the battle of Rock Creek, where he commanded the State forces after the death of the lamented Holloway, and at Carthage, where he won un-fading laurels by the display of extraordinary coolness, courage and skill. He fell at the head of his brigade; wounded in three places, and died just as the victorious shouts of our men began to rise upon the air." The losses of the armies, killed, wounded and missing, were about equal. The total Federal loss was 1,317; the total Confederate loss, 1,218. In the engagement between Mcintosh and Plummer, the Federals lost 80 and the Confederates 101. In the attack on Sigel, the Confederate loss was small, but Sigel's loss was heavy--not less than 300. The loss of the Missourians on Bloody Hill was 680; the loss of the Arkansans there--Churchill's and Gratiot's regiments and Woodruff's battery--was 308. The loss of both sides on Bloody Hill was, Missourians and Arkansans, 988; Federals, 892. Well may the historian say: "Never before--considering the number engaged --had so bloody a battle been fought on American soil; seldom has a bloodier one been fought on any modern field." The Federals retreated to Springfield leaving the body of their dead general on the field. By order of General Price the body was identified and delivered to his friends, who came to ask for it under a flag of truce. But it was again left behind, when they abandoned Springfield, and was taken in charge of and given decent burial by Mrs. John S. Phelps, the wife of a former representative in congress from that district, then an officer in the Federal army. The fruits of this splendid victory were lost. As soon as it was known that the Federals were retreating, General Price urged General McCulloch to make pursuit, but McCulloch declined. The Federals had lost heavily in the battle and were badly demoralized. They had a long, difficult road to travel before they could reach assistance at Rolla. The road to Rolla ran through rugged, broken country, with many streams to ford or ferry, and was already crowded with hundreds of Union refugees along with their teams and families, who were fleeing in terror from McCulloch and his Texans. McCulloch refused afterward to make even a pretense of pursuit. The dead were buried where they fell. General Price was in pursuit but lacked the necessary ammunition to make the pursuit alone. All in all it was a fruitless victory for the South.

Saturday, March 24, 2007

Virginia Seizes Harper Ferry - April 18th & May 23rd, 1861

Back on October 16th in 1859 the radical abolitionist John Brown led a group of 18 men in a raid. Ten of the eighteen men were black. Assisting fugitive slaves was illegal and unacceptable in nearly all white communities. When John Brown attacked Harper's Ferry he captured enough weapons to create a slave uprising. Militia quickly stepped in and troops commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee captured most of the raiders. Brown was tried for treason by the State of Virginia, convicted, and hanged in nearby Charles Town. The failed raid was an introduction for Civil War that was to follow.

When Virginia seceded from the Union in April of 1861 the US garrison attempted to burn the arsenal and destroy the machinery. Locals saved the equipment, which was later transferred to a more secure location in Richmond. Arms production never returned to Harpers Ferry. A student company from the University of Virginia was one of the militia units moving toward Harpers Ferry. Among its ranks was a 17 year old boy named Robert E. Lee, Jr., son of the future Confederate general.

Harpers Ferry was a strategic location on the railroad at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. Both Union and Confederate troops moved through Harpers Ferry with the location changing control many times throughout the war.

When 37 year old Thomas J. Jackson arrived at Harpers Ferry, Va., on April 30, 1861, he had not yet become famous. He was known only as a professor. The town had just recently been taken over by Confederate state forces, and Jackson had been sent to organize and command the new recruits. He found the double tracks of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad that ran through Harpers Ferry were still being heavily used, transporting thousands of tons of coal and supplies daily between the Union East Coast and the Midwest. A few weeks after taking command, Jackson informed the president of the railroad that he would have to stop running trains through Harpers Ferry at night because it disturbed the sleep of his soldiers. The schedules were changed so the trains passed through town only during the day. But Jackson was not satisfied, saying the trains interfered with his men's drill. The railroad and Jackson then reached a compromise, the trains would pass through town only between 11:00 A.M. and 1:00 P.M. But during those two hours the traffic was very heavy in both directions. On May 21 at 11:00 A.M., Jackson had opposite ends of each side of the 31 mile stretch of double tracks barricaded and trains could enter a section of track, but they could not leave. At 1:00 P.M., he had the tracks at both ends torn up so that 42 locomotives and 386 cars were now the property of the Confederacy. From Harpers Ferry, there was only a spur track that ended at Winchester, Virginia still 20 miles from Staunton, the closest track connecting with the Southern rails. Jackson had his men haul 14 of the locomotives and many of the cars overland to Staunton. Jackson purchased a runt of a horse that was found in one of the captured cars and intended to give it as a gift to his wife. Jackson grew so fond of the nag, he named it Little Sorrel, and rode it during the war.

When Virginia seceded from the Union in April of 1861 the US garrison attempted to burn the arsenal and destroy the machinery. Locals saved the equipment, which was later transferred to a more secure location in Richmond. Arms production never returned to Harpers Ferry. A student company from the University of Virginia was one of the militia units moving toward Harpers Ferry. Among its ranks was a 17 year old boy named Robert E. Lee, Jr., son of the future Confederate general.

Harpers Ferry was a strategic location on the railroad at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. Both Union and Confederate troops moved through Harpers Ferry with the location changing control many times throughout the war.

When 37 year old Thomas J. Jackson arrived at Harpers Ferry, Va., on April 30, 1861, he had not yet become famous. He was known only as a professor. The town had just recently been taken over by Confederate state forces, and Jackson had been sent to organize and command the new recruits. He found the double tracks of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad that ran through Harpers Ferry were still being heavily used, transporting thousands of tons of coal and supplies daily between the Union East Coast and the Midwest. A few weeks after taking command, Jackson informed the president of the railroad that he would have to stop running trains through Harpers Ferry at night because it disturbed the sleep of his soldiers. The schedules were changed so the trains passed through town only during the day. But Jackson was not satisfied, saying the trains interfered with his men's drill. The railroad and Jackson then reached a compromise, the trains would pass through town only between 11:00 A.M. and 1:00 P.M. But during those two hours the traffic was very heavy in both directions. On May 21 at 11:00 A.M., Jackson had opposite ends of each side of the 31 mile stretch of double tracks barricaded and trains could enter a section of track, but they could not leave. At 1:00 P.M., he had the tracks at both ends torn up so that 42 locomotives and 386 cars were now the property of the Confederacy. From Harpers Ferry, there was only a spur track that ended at Winchester, Virginia still 20 miles from Staunton, the closest track connecting with the Southern rails. Jackson had his men haul 14 of the locomotives and many of the cars overland to Staunton. Jackson purchased a runt of a horse that was found in one of the captured cars and intended to give it as a gift to his wife. Jackson grew so fond of the nag, he named it Little Sorrel, and rode it during the war.

Friday, March 23, 2007

Sutler's List

THE PRODUCTS OF THE TOWN, FOR THE YEAR 1859.

Butter, number of lbs………………..2,261Cheese, number of lbs……………..16,000Hay, number of tons………………...1,275Wheat, number acres………………..5,112Corn, number acres…………………...830Oats, number acres………………….1,133Potatoes, number acres…………………59Cattle, value on hand………..……$20,833Hogs, value on hand………………...2,857Sheep, value on hand……………..…2,034

valuation………..$2,971valuation…………...110valuation…………7,063valuation………..63,707valuation………..13,745valuation…………8,299valuation…………3,906value slaughtered...1,108value slaughtered...7,417value slaughtered…..180

Horses and Mules, value……………………………………..……10,979Wool, value…………………………………………....……………......639Apples, value…………………………………...…………………...…...32Beans and Peas, value……………………………………….………...128Barley, value………………………………………………………….....782Clover Seed, value…………………...………………………………......12Buck Wheat, value………………………...…………………………....127

Butter, number of lbs………………..2,261Cheese, number of lbs……………..16,000Hay, number of tons………………...1,275Wheat, number acres………………..5,112Corn, number acres…………………...830Oats, number acres………………….1,133Potatoes, number acres…………………59Cattle, value on hand………..……$20,833Hogs, value on hand………………...2,857Sheep, value on hand……………..…2,034

valuation………..$2,971valuation…………...110valuation…………7,063valuation………..63,707valuation………..13,745valuation…………8,299valuation…………3,906value slaughtered...1,108value slaughtered...7,417value slaughtered…..180

Horses and Mules, value……………………………………..……10,979Wool, value…………………………………………....……………......639Apples, value…………………………………...…………………...…...32Beans and Peas, value……………………………………….………...128Barley, value………………………………………………………….....782Clover Seed, value…………………...………………………………......12Buck Wheat, value………………………...…………………………....127

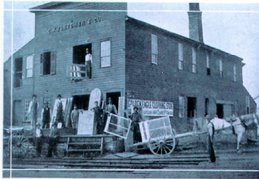

Town of Mackford, Wisconsin

TOWN OF MACKFORD

To the north is the town of Green Lake. To the east is Fond du Lac County. To the South is Dodge County. To the west is the town of Manchester. This is the lush valley of the Grand River. One mile from Mackford is Markesan.

The first house in town was built in 1836 by H. McDonald. He broke up the land and raised the first staples on his farm. The first saw mill built in the county, was erected in 1843, by H. McDonald and in 1850 McDonald, Carhart and White erected a four story stone grist mill. A number of dwellings were added and the population of the village rose to 150 souls. The town derives its name from the first part of McDonald's name and a crossing place over the river. McCracken's mill was built in 1848 and a grist mill was added in 1855. It rose three stories high, with a capacity of seventy barrels of flour in twenty-four hours. Austin McCracken was the builder and owner of these mills. His homestead was across from the mills where he also owned the adjacent lands. From the mills to the village, it is about one and a half miles. In the villiage of Mackford there was a Post-office, a Mercantile, a Wagon Shop, a Blacksmith Shop, a Carpenter Shop, two Cooper Shops, a tailor, two Shoe Makers and the District's School. Land lying north of the river was open and somewhat broken rising gently. Lands to the north of the village had sandy soil and clay loam making for good cultivation. Leaving Mackford village to the south is a high hill covered with oaks, clay loam soil and then prairie as far as the eye can see. One of the most beautiful prairies in the midwest, it sways pleasantly like the roll of the sea, wave after wave falling to the horizon for miles upom miles. The north and west are fringed with trees, several glades and homesteads and farms dot the landscape. Here the bountiful increase of the land lays in golden stacks and field upon field of ripening corn sways in the prairie wind. Providence has directed the wandering footsteps of the pioneers to so rich a heritage as this. Here the heart of man may rejoice in his destiny. Here is a land to supply the wants of the body and the hopes of the mind. Rich furtile soil await the labor of a man's hand to reap the reward of hard work. The valley of the Grand River a mile wide, it is bordered by marsh and timber, on the south by hill that open to the prairie. Timber land rises from Grand River to Lake Maria to the west of the prairie. Good water can be found all over the town and is from six to ninety feet in depth. Lake Emily lies to the south of town, Lake Maria is to the southwest and covers about six hundred acres, one-half of which is in the town of Manchester. There is no known outlet to this lake. At high water it often overflows. The fish in this lake were killed out in the hard winter of 1848. They were smothered, as is believed, as the lake was entirely frozen over and a heavy body of snow some four feet deep. In the spring winrows of fish were cast ashore, since which time there has been no fishing. At it's greatest depth the lake is thirty feet. About three-fourths of this town is under cultivation. There are Christians churches for public worship nearby at Alto, Whitewater and Markesan. The Town of Mackford was organized in 1849.

The inhabitants are all Yankees!

To the north is the town of Green Lake. To the east is Fond du Lac County. To the South is Dodge County. To the west is the town of Manchester. This is the lush valley of the Grand River. One mile from Mackford is Markesan.

The first house in town was built in 1836 by H. McDonald. He broke up the land and raised the first staples on his farm. The first saw mill built in the county, was erected in 1843, by H. McDonald and in 1850 McDonald, Carhart and White erected a four story stone grist mill. A number of dwellings were added and the population of the village rose to 150 souls. The town derives its name from the first part of McDonald's name and a crossing place over the river. McCracken's mill was built in 1848 and a grist mill was added in 1855. It rose three stories high, with a capacity of seventy barrels of flour in twenty-four hours. Austin McCracken was the builder and owner of these mills. His homestead was across from the mills where he also owned the adjacent lands. From the mills to the village, it is about one and a half miles. In the villiage of Mackford there was a Post-office, a Mercantile, a Wagon Shop, a Blacksmith Shop, a Carpenter Shop, two Cooper Shops, a tailor, two Shoe Makers and the District's School. Land lying north of the river was open and somewhat broken rising gently. Lands to the north of the village had sandy soil and clay loam making for good cultivation. Leaving Mackford village to the south is a high hill covered with oaks, clay loam soil and then prairie as far as the eye can see. One of the most beautiful prairies in the midwest, it sways pleasantly like the roll of the sea, wave after wave falling to the horizon for miles upom miles. The north and west are fringed with trees, several glades and homesteads and farms dot the landscape. Here the bountiful increase of the land lays in golden stacks and field upon field of ripening corn sways in the prairie wind. Providence has directed the wandering footsteps of the pioneers to so rich a heritage as this. Here the heart of man may rejoice in his destiny. Here is a land to supply the wants of the body and the hopes of the mind. Rich furtile soil await the labor of a man's hand to reap the reward of hard work. The valley of the Grand River a mile wide, it is bordered by marsh and timber, on the south by hill that open to the prairie. Timber land rises from Grand River to Lake Maria to the west of the prairie. Good water can be found all over the town and is from six to ninety feet in depth. Lake Emily lies to the south of town, Lake Maria is to the southwest and covers about six hundred acres, one-half of which is in the town of Manchester. There is no known outlet to this lake. At high water it often overflows. The fish in this lake were killed out in the hard winter of 1848. They were smothered, as is believed, as the lake was entirely frozen over and a heavy body of snow some four feet deep. In the spring winrows of fish were cast ashore, since which time there has been no fishing. At it's greatest depth the lake is thirty feet. About three-fourths of this town is under cultivation. There are Christians churches for public worship nearby at Alto, Whitewater and Markesan. The Town of Mackford was organized in 1849.

The inhabitants are all Yankees!

Thursday, March 22, 2007

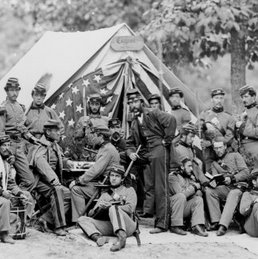

Fort Sumter - April 12th to April 14th, 1881

On April 12th, 1881 Confederate batteries opened fire on the Federal fort, which was unable to effectively defend itself. At 2:30 p.m., April 13th, Major Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter, evacuating the garrison on the following day.

The bombardment of Fort Sumter was the first military action of the American Civil War. Although there were no casualties during the bombardment, one Union artillerist was killed and three wounded (one mortally) when a cannon exploded prematurely while firing a salute during the evacuation on April 14th. Private Daniel Hough lost his life and was the first casualty of the Civil War. He succomb to the same fate as Stonewall Jackson, shot by friendly fire.

The bombardment of Fort Sumter was the first military action of the American Civil War. Although there were no casualties during the bombardment, one Union artillerist was killed and three wounded (one mortally) when a cannon exploded prematurely while firing a salute during the evacuation on April 14th. Private Daniel Hough lost his life and was the first casualty of the Civil War. He succomb to the same fate as Stonewall Jackson, shot by friendly fire.

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

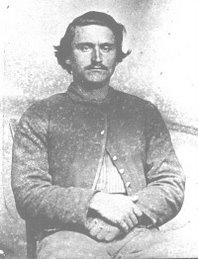

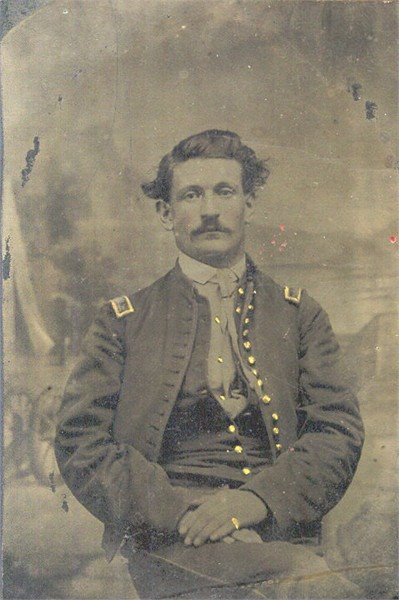

The Story Begins...

This story begins out on the east coast in the mid 1880's prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. It is the story and struggle of various members of my family tree as they moved to the Midwest to take hold of their share of the frontier that was then America. Every single person in my family for generations upon generations has been from the North, blue bellied Yanks through and through!

The Wright's ventured out to the big woods of Wisconsin from Erie, New York and settled around Mackford in Green Lake County where they began to farm.

The Rinehimer's came from Hanover, Pennsylvania and settled in Elgin, Illinois where they ran a sawmill.

The Woods also came to Wisconsin to farm from Franklin, Pennsylvania. They had married into the women folk of the Fletcher Clan from Cambridge, England. They made the journey to stake a claim in midwest soil with their eight children in toll. Along with the Fletchers the Tuck family tagged along from Wyoming County, PA.

The Hawkins were from Providence, Rhode Island and came to the furtile dirt of Wisconsin to farm.

The Spees family came from Maine and settled in Plainfield, Wisconsin where they also took up farming.

The Stevens family traveled to Elgin, Illinois via bean town but even before then they were from Maine. The Radcliffe's were also from Maine but had of late resided in Boston, Mass.

The Hawns had already resided on the frontier in Neosho, Wisconsin for a good long time and their eldest lad married one of the pretty Wood girls.

These families were to become linked in more ways then one...

The Wright's ventured out to the big woods of Wisconsin from Erie, New York and settled around Mackford in Green Lake County where they began to farm.

The Rinehimer's came from Hanover, Pennsylvania and settled in Elgin, Illinois where they ran a sawmill.

The Woods also came to Wisconsin to farm from Franklin, Pennsylvania. They had married into the women folk of the Fletcher Clan from Cambridge, England. They made the journey to stake a claim in midwest soil with their eight children in toll. Along with the Fletchers the Tuck family tagged along from Wyoming County, PA.

The Hawkins were from Providence, Rhode Island and came to the furtile dirt of Wisconsin to farm.

The Spees family came from Maine and settled in Plainfield, Wisconsin where they also took up farming.

The Stevens family traveled to Elgin, Illinois via bean town but even before then they were from Maine. The Radcliffe's were also from Maine but had of late resided in Boston, Mass.

The Hawns had already resided on the frontier in Neosho, Wisconsin for a good long time and their eldest lad married one of the pretty Wood girls.

These families were to become linked in more ways then one...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)